The academically top-ranked charter school in Colorado Springs has displayed a pattern of discrimination against children with special needs and shirked its lawful responsibilities, some parents and teachers are alleging.

The Vanguard School’s high marks on standardized testing they say are partly the result of cherry-picking students most likely to succeed under its rigorous curriculum while leaving behind those in need of disability accommodations.

Fifty-five people with ties to The Vanguard School — including an overlapping mixture of 22 current and former employees, 15 alumni and 28 parents — spoke to The Gazette of a culture in which those who broke from a so-called “Vanguard box” were dismissed or punished, especially those with special needs.

They described instances in which special education students were treated as “an inconvenience,” a sentiment they said was enabled by school officials.

“It felt to me almost deliberate, where the levels of academic pressure were so high, but the support systems and the resources that students needed were so low, that it almost became kind of its own filtration system,” said Vanguard alumna and former junior high English teacher Natasha Dowdall.

Four families claim their children were denied enrollment due to special education needs. Another family said they chose not to explore an Individualized Education Program, or IEP, after administrators allegedly said there would be no room for their child if they did. The legally binding contract ensures a child with identified needs or disabilities receives specialized instruction and related services.

Michael Claudio, the assistant superintendent of Vanguard’s chartering body, Harrison School District 2, said the district’s Special Education Department is not aware of complaints about children being denied enrollment for basic accommodations, as parents and teachers allege.

“Vanguard has fully complied with IEPs and sought what is best for our students — all students, including those with special needs,” current Vanguard Executive Director Renee Henslee wrote in a statement. “I have seen no evidence of any of these allegations, nor did I see evidence in my previous role as elementary principal.”

The concerns expressed by the teachers, alumni and parents date back to at least 2015 and are as recent as 2022. Most teachers and parents who made allegations against Vanguard’s special education practices have since left the school.

Teachers speak out

Vanguard’s only special education teacher at the time said she had witnessed enough “active discrimination” by the spring of 2017 that she sent a letter to Vanguard’s department of human resources and to its then-chartering district, Cheyenne Mountain School District 12. She outlined the issues she’d seen, some of which she said she believed were illegal.

The teacher, who wished to remain anonymous to protect her family, said faculty complained about accommodating students’ IEPs, even pledging outright not to. Students who struggled were labeled “lazy.” Nothing changed despite reporting several instances of discrimination to then-Executive Director Colin Mullaney, the teacher claimed.

The former teacher said her hands were tied by an administration that was unwilling to properly accommodate its students.

“(Mullaney) wanted me to remove accommodations for it to be easier to fail students. … He at one point said that he wanted to give kids who had modified curriculums certificates instead of diplomas. He wanted on their diploma it to be noted that they did not receive the standard Vanguard diploma,” the former special education teacher said. “He said, ‘It’s my school, it’s my rules. You will listen to those rules, or you will no longer be here.’ Two weeks later I quit."

Mullaney left Vanguard in 2021 to become an administrator at Hillsdale College in Michigan. He declined The Gazette's request for comment on this story.

“The IEPs and 504s that were in place were almost disregarded in certain senses," said the former teacher Dowdall. "There were teachers who just completely dismissed them or who felt they were more of an inconvenience.”

Section 504 is a federal civil rights law that ensures a child with a disability has equal access to education.

“It’s students who were struggling the most who seemed to leave the school, and maybe people weren’t sad about it.”

She wasn’t alone in her calls for change.

Molly Fiedler, a former junior high English teacher and certified special-needs educator who left Vanguard in 2017, said she echoed those concerns and was “constantly” telling school leaders they were breaking IEP laws.

“I was told time and time again, ‘You have to have a more positive attitude, you have to be more supportive of the school, you need to keep your opinions to yourself,’” Fiedler said. “There was no real fair way or any way in which they allowed teachers to teach to the kids who needed any kind of supports.”

In a 2020 letter to the Colorado High School Activities Association in support of a student, a former high school teacher outlined ways “in which The Vanguard School failed (her student) and continues to disenfranchise students with disabilities and students of diverse backgrounds.”

The teacher, who also asked not to be identified for fear of retribution, said she heard Mullaney tell the school counselor he did “not want students coming to (her) with mental health problems” and to maintain distance. That counselor posted a sign discouraging students from seeking counsel without an appointment.

Teachers at the school doubted the validity of mental disorders and learning disabilities and “purposefully failed to support student accommodations,” the former high school teacher wrote in the letter. It was common practice, too, to place students in the hallways during passing period if their IEPs required extended time to finish exams, she said.

“Those students slip through the cracks uniformly and in high numbers. I think it was kind of like the approach was to offer the bare minimum and they’ll leave, and then we won’t have to deal with those students. That’s never spoken, but like, you just, you know, right? Those students just don’t get support,” she said.

For former junior high biology teacher Sarah Nupen, who had not previously worked in a classroom before teaching at Vanguard, the school’s emphasis on grit initially was a draw. Her perception changed in 2017 after helping with the high school play.

Nupen saw the older sibling of one of her students excel at singing and acting only to crumble under academic pressures because he lacked sufficient support. Grit, she said, was weaponized.

“I couldn’t get behind kids who were academically struggling being told they were not good enough, or that they just had to work harder to be successful as opposed to being successful in different ways. The idea there's so much reward in the struggle started to become a really hard concept for me,” Nupen said. “That year I resigned.”

Some teachers traced their concerns back to former director Mullaney.

“If he could possibly have avoided it, he wouldn’t have had any IEP or 504 special education students. I’m absolutely certain that that’s true,” former high school history teacher Valerie Younger said.

An aerial photograph of The Vanguard School in December. The Vanguard School is the academically top-ranked charter school in Colorado Springs and one of the top ranked in the state.

Graduation exercises for The Vanguard School were held in May 2015 at The Vanguard School.

Mullaney allegedly likened enrolling a student with multiple disabilities to “opening the floodgates,” according to longtime former elementary school teacher Jennifer Sweet. Since they were a charter school with limited funding, they lacked money to properly accommodate many disabled children in need of special services, he allegedly told her.

“Schools like (Vanguard) thrive on rigor, and they want to be known as the most rigorous,” the former special education teacher said. “That’s the classical model: You work hard, you did this rote memorization, and kids rarely fit that mold. When they do fit that mold, they develop anxiety issues because they need perfection. When they don’t fit that mold, they develop depression issues because they’re told they’re not good enough. There was no winning. No one won in that environment.”

One former Vanguard educator said she had heard notes of improvement surrounding the school's special education culture since Mullaney's departure. Again, Mullaney declined comment.

Changes in the system

Colorado was an early adopter of school choice, in 1993 becoming the third state in the nation to legalize charter schools.

Thirty years later, Colorado has 262 charter schools, which are publicly funded but are granted more autonomy than traditional public schools in governance, curriculum, budget, staffing and innovation.

Some of the complaints being levied against Vanguard are not uncommon. They come amid a long-running political battle between traditional public schools and charter schools over students and the dollars they bring. That feud has included claims from teachers unions that charters screen their students through complex application processes that can make it tough for students who struggle with disabilities, limited English skills, academic deficits or chaotic family lives.

Charter advocates say it's a fair fight because both types of schools are free and open to all, and many charters specialize in serving low-income and minority children.

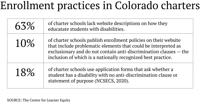

But Colorado charter schools have enrolled students with disabilities at a lower rate than the state’s average for traditional public schools — and at a lower rate than charter schools in most other states, according to a study by the Center for Learner Equity, which was released in November 2020.

Nationwide, traditional public schools enroll students with disabilities at a rate roughly two percentage points higher than their charter school counterparts, the study said.

Statewide in the 2019-2020 academic year, students with a disability comprised 11.6 % of the student population at traditional public schools, while students with disabilities provided 7.4% of charter school enrollment.

Charter schools have seen a slight improvement but still nowhere near the national average.

In the 2022-23 school year, traditional public school enrollment consisted of 13.1% of students with disabilities, while charter school enrollment stood at 8.3 % of students with disabilities, according to the Colorado Department of Education.

Changes have been made to equalize enrollment.

The Colorado State Board of Education adopted new guidance last year, after the U.S. Department of Education’s Office for Civil Rights received complaints about 29 Colorado charter schools’ practices in admitting students with disabilities.

Five of the schools that were the subject of concern were in El Paso County. However, Vanguard was not on the list.

The local schools investigated were:

• New Summit Charter Academy in Academy School District 20, where 5.1% of its enrollment consisted of students with disabilities;

• The Classical Academy in Academy D-20, 4.1%;

• Liberty Tree Academy in School District 49, 8.3%;

• Pikes Peak School of Expeditionary Learning in School District 49, 11.6%;

• Monument Academy in Lewis-Palmer School District 38, 6.2%

Meanwhile, at Vanguard Elementary School in 2019-2020, 3.2% of students enrolled had disabilities.

Percentages were not provided for Vanguard’s middle and high schools in that year, as their numbers qualified as “privacy-protected” in the study, meaning the number was few enough to suppress the data. Sixteen charter schools in the state fell into that category.

Colorado’s new guidance clarified that schools cannot ask on their applications whether students require special education services, to remove the possibility of a child’s disability or need to learn English becoming an admission factor.

Rather, any inquiries about a student’s disability status shall not occur until “post admissions.”

A school or district is not allowed to deny enrollment to special needs students without first convening a team that includes parents to determine whether the school of choice can implement the Individualized Education Program (IEP), according to the state's updated guidelines. Only under extreme circumstances might it be appropriate to override a parent’s school choice decision, and such a determination must be thoroughly explained in writing, the guidelines stipulate.

In another charter school scrutiny case, Vega Collegiate Academy in Aurora faced shut down four years ago, after ranking first for math growth in the state in 2018 and second in 2019.

The board of Aurora Public School voted to close Vega in February 2019, saying the school violated its charter contract with the district by not adequately serving students with special needs.

The board reversed the decision that May, after the State Board of Education asked the district to reconsider, citing students’ high performance.

The district issued a corrective action plan and conducted a third-party investigation into the claims about special-education deficiencies. The school agreed to a corrective action plan and remains open today.

Getting in

Vanguard’s high school campus consistently ranks first in Colorado Springs for state testing performance, graduation rate and college preparation, according to annual tabulations by U.S. News and World Report. Vanguard regularly places in the state’s top 10, most recently ranking seventh in Colorado and receiving a gold medal nationally.

Lower Vanguard grades also receive praise for their rigor, yet school leaders do not consider admission an achievement.

The Charter Schools Act and State Board Rule prohibit charter schools from basing their admission decisions on academic ability. A charter school may create eligibility thresholds for enrollment that are consistent with the charter's area of focus or grade levels, according to the Colorado Department of Education, but the school’s methods for determining eligibility cannot be "designed, intended, or used to discriminate on the basis of a child’s knowledge, skills or disability."

Director of Operations Jeff Yocum said they have waitlists “at times” that vary greatly from year to year and grade to grade, depending on how many families apply each year. A family’s position on that list is determined either by lottery or date of application.

State law bars public schools, including charters, from basing enrollment on entry exam scores. The law does not bar Vanguard’s placement exams, however, which determine grade level. Placements are re-evaluated via end-of-year mastery exams that sometimes deem students unprepared to advance to the next grade.

Vanguard does not allow parents to waive its determinations, Executive Director Henslee said, because they are in students’ long-term best interests.

“Our approach to placement testing is designed to place students at the right grade level so that they have the best chance of succeeding and getting the most out of their education,” Henslee said in a written statement. “Placing the student in a grade beyond his or her abilities is far more likely to result in the student giving up or failing out."

But parents and teachers allege the school’s enrollment system is nevertheless rigged in favor of high performers, weeding out those with special needs who don’t naturally meet its high standards.

“I know from being in education for 25 years that their scores are manipulated. Not that they’re not true scores of their students, but they’re manipulated because they almost — the system helps them choose their students,” said a former Vanguard employee of nearly a decade who requested to remain anonymous due to her current role as a school principal.

“I hate to use this word, but that’s how I feel, I feel very strongly that their enrollment practices are discriminatory.”

Charter schools take several approaches to keep out students with disabilities, said Alex Medler, Boulder-based executive director of the National Network for District Authorizing, which supports state-level initiatives to strengthen charter school authorizing practices. Most straightforward, they can simply deny special education students, Medler said, which he described as clearly illegal. Schools are often more covert, though.

Schools might tell parents they are not equipped to provide services under a child’s current IEP and suggest they either relinquish their plan or go elsewhere, Medler said. They might also enroll a child and fail to provide services, or they might provide services but refuse to admit the student to the next grade level, thereby weeding them out over time. Former Vanguard parents and teachers described personal accounts of each scenario.

A former front office worker, who also asked to remain anonymous for fear of retaliation from the Vanguard community, said her son’s 2017 enrollment was contingent on repeating seventh grade. She conceded, but after he again performed poorly on the school’s end-of-year mastery exam, administrators said he must repeat the grade for a third time or leave Vanguard.

She transferred her son in 2018 to another district, which identified a learning disability and advanced him to the next grade level with a new IEP. She quit her job at Vanguard that same year.

“That’s how they keep a lot of students who don’t academically perform well initially out of Vanguard, which is in Vanguard’s best interest because they don’t have teachers who can teach differentiated lessons to support the kids who don’t fit in the box Vanguard has in that age group,” former teacher Nupen said. A kid might test into seventh grade at age 14, she said, “so at age 15 if they failed, they could be in seventh grade again,” but their cohorts would be much younger. “No child would be OK with that for very long,” she said.

Yellow flag, red flag

Emails obtained by The Gazette show one student tested into his grade of choice and was directed to the enrollment office in 2020. Unlike his sibling, however, he would never be offered a spot at Vanguard. His mother, who requested anonymity to protect her child’s identity, said the school informed her it had maxed out its IEP caseload and could not enroll her son.

His IEP accommodations included extra time on assignments, frequent breaks during tests and individualized or small group work “as needed,” the IEP shows.

“Those are all things that should be happening in general education,” said Wendy Tucker, a lawyer and the senior policy advisor for national nonprofit Center for Learner Equities. Tucker’s work focuses on ensuring students with disabilities have access to high quality schools in choice environments. “That’s basic education 101. If those are the kids they’re saying no to, then that’s disturbing.”

Public schools cannot cap the number of disabled students they will enroll or establish a quota, Tucker said. There is no such thing as “maxing out” on the number of IEPs a school can offer, although it is true that resources sometimes run thin.

Denying a special education student enrollment without first assembling an IEP team, as multiple Vanguard parents allege, is illegal, said Lakewood-based charter school lawyer Bill Bethke.

Among the four families who claim that their children were denied enrollment due to their special education needs, that is, having an IEP or 504 plan, and the additional family that said they chose not to explore an IEP after administrators allegedly said there would be no room for their child if they did, some said Vanguard never sought specifics of their support plans — simply having one was grounds for rejection.

The families said their child’s plan included standard accommodations that Bethke and Tucker said every school should be equipped to meet, like reading exams to students aloud or offering a quiet room to work. When asked about the assertions of the five families that their students were denied admission because of their learning disabilities, the Vanguard School declined to discuss any particular set of students, past or present, citing federal educational privacy laws.

Only 48 of roughly 1,600 K-12 students at Vanguard were on IEPs last year, representing about 3% of its student population, according to data provided through an open-records request The Gazette filed. The year prior, that number was 41, or 2.5%.

A typical IEP average for public schools is 9% to 12% of a school’s population, according to Bethke. With that average, Vanguard should be able to accommodate about 160 IEPs at any given time, on average.

Said Bethke, “That’s a school that should be thinking hard about, ‘Can we serve more students with disabilities?’”

Said Tucker, “If I saw that, I’d say they’re counseling families out. They’re discriminating.”

Because public school districts are required by law to use blind enrollment lotteries and cannot use disabilities as an enrollment factor, their percentage of students with IEPs should more closely align with the percentage of kids with disabilities in their community.

District-wide, about 18% of Harrison D-2 students are on an IEP, or 14% when its authorized charter schools are factored in. The district has no expectations of how many IEPs any given school should accommodate, said Claudio, the assistant superintendent.

“It would not be appropriate for a school to accept a student knowing that (the school) cannot serve the IEP. That is not what is best for the student,” Claudio said.

“A child’s district of residence is required to provide a student with the services outlined in the IEP, though it may not be at their home school or school of choice,” he said.

The public school district within which the child lives is required to serve the child no matter the details of an IEP, while the district that the child might otherwise want to attend is not.

Henslee said parents “may be making incorrect assumptions about the situation.”

IEPs are only reviewed after a student is enrolled. The school’s entire IEP team then determines whether it can service the plan. Decisions “cannot be made unilaterally by any one member of the team,” she said. Though they strive for consensus with parents, D-2 has the ultimate say on whether the school can best meet their needs.

Henslee noted a policy that was in place “several years ago” while Vanguard was chartered under Cheyenne Mountain D-12.

“... there was a period of time when the district and Vanguard were not able to approve non-resident enrollment for new students due to caseloads having met capacity. All out-of-district requests were put on a waiting list. If space became available, priority was given to non-resident students based on their original application date and wait list number. IEPs were not reviewed until a spot became available,” Henslee said.

Such a policy would not hold up under the State Board of Education’s guidance today, according to Medler of the National Network for District Authorizing. Medler has led efforts in Colorado for the past five years to increase access to charter schools for students with disabilities.

At a minimum, a public school suggesting to parents it cannot accommodate an IEP without first scheduling a formal meeting is an “outdated” practice long thought to be a bad one, attorney Bethke said. If a school outright tells families it won’t service an IEP — especially without having read its specifics — “that’s clearly illegal.”

Positive experiences

Tiffany, a parent of four Vanguard students, some of whom have an Individualized Education Program, said while she knows some families have had issues with Vanguard, she has not had any problems in the four years her children have been attending the charter school.

In fact, “Vanguard has taken the initiative to put IEPs in place when some of my children didn’t have them and were struggling,” she said. “The school recognized the struggle and chose to intercept it with me.”

Advocacy on the part of teachers at the middle school led to one of her children getting help that was needed for learning, Tiffany said, asking that her last name not be used for privacy reasons.

And when her high school daughter suffered a concussion earlier this year and was having a hard time participating in normal class activities, the school provided a medical IEP to ease the situation.

“Overall, nearly every teacher jumped on board and went above and beyond to help her succeed,” Tiffany said.

Tiffany said she did not want to discount the experiences of other parents who have encountered difficulties.

“I know many parents have had issues with IEPs and communication from the school, and I am no exception,” she said. “Nothing is ever perfect, and there are some issues that are downright wrong, and I hope those get solved for those parents.

“But overall, I have been pleased with my experience with the student services team.”

Vanguard mom Sonie Munson thinks that some parents may not understand the system or be willing to work within its parameters.

Her son, who has special needs, has attended six different schools because of her husband’s military assignments, and the family’s experience at Vanguard has been very positive, she said.

“This school is one of the better ones we’ve attended,” Munson said. The main reason: “It definitely feels like an IEP team. Everyone communicates well.”

“I was in literal tears of joy during our annual IEP meeting last year; it was by far the easiest one we have done, as the other team members were adding and advocating for more properly adjusted supports for our child,” she said. “It was amazing and something we’ve never experienced before.”

Their child is thriving, Munson said, and now needs less assistance than before because of the structure and routine of the school’s model.

“If you have an IEP and you have a problem, you have to adjudicate it correctly and go through the formal system,” Munson said. “We did that at another school, and it went all the way to the state’s ombudsman because what our son needed wasn’t there. The state said, ‘Let’s fix it.’

Families denied

Vanguard does not cap the number of IEP students it enrolls, Henslee said.

“Even so, it is appropriate for a school to tell a parent if it lacks the capacity to support a student’s services because it doesn’t have the personnel to provide the service that is needed,” Henslee said.

Only in rare situations might it be appropriate to send a child elsewhere, Bethke said. A student with severe cognitive disabilities or a student with behaviors that are very difficult to manage might necessitate such a consideration.

In those situations, schools must hold meetings with the family and IEP team to try to reach a consensus on how best to serve that student, according to Bethke. An email or phone call from a school official does not suffice.

“It’s really clear that if you're going to move a kid from the school that their parents want to enroll them in due to what’s on their IEP or their disability, you need to have a meeting to do that,” Bethke said. “That’s what’s supposed to happen.”

Several families allege Vanguard denied their children enrollment without scheduling such a meeting.

“I was flat out told (my daughter) was not getting in because of her IEP because they could not meet her accommodations,” said parent Leanne Bowen. “I had to fight them tooth and nail. I threw a fit. I threatened them with the media. I threatened them with lawyers. I threatened them with every single weapon I had in my armory.”

Bowen met her ex-husband two decades ago while attending Vanguard, then called Cheyenne Mountain Charter Academy. The two experienced the school’s quality firsthand and wanted better for their family than they felt most public schools could provide. They were adamant about sending their kids to Vanguard, she said, yet the school met their daughter with resistance.

After it had already enrolled her daughter, Vanguard allegedly informed Bowen by phone that it was walking back its decision due to the young girl's 2018 IEP. The plan required limited speech services and catered mostly to social-emotional needs rather than academic ones. Her family lived within district boundaries at the time.

Vanguard acquiesced after heavy pushback, later telling Bowen her daughter did not need an IEP after all, she said. She would withdraw her daughter earlier this year. Bowen said the matter soured her to the idea of enrolling her son, who has greater needs.

“I just knew after the debacle with (my daughter), there was just no way,” Bowen said. “There was no way I was going to be able to put him in Vanguard.”

Heather Kershner, a former PTO co-vice president and parent of four former Vanguard students, said upon inquiring about a potential IEP for her son, administrators said they could not accommodate or put one in place. If one was necessary, the Kershners would need to look elsewhere for school.

Her son’s therapist recommended minor accommodations, but Kershner said they chose not to explore them in order to enroll him at the elite school.

The Kershners withdrew all their children in 2022 due to Vanguard’s “exclusive” environment, where Kershner said difference of any sort was unwelcome. Again, Vanguard declined to discuss specific students, citing federal educational privacy laws.

‘Impossible situation’

The Gazette shared with Vanguard administrators a comprehensive list of concerns brought by current and former employees and families but did not share all names of those who voiced them. Henslee said the school is “being put in an impossible situation” and “can’t respond to such vague allegations.”

Henslee, who assumed the role of executive director in 2021 as the district shifted to D-2 oversight, said she has never heard teachers express concern over IEP practices. The school has never purposefully failed to meet an IEP, watered down accommodations or tried to make it easier to fail special education students, she said.

Staffing and funding challenges plague special education offerings at schools across the state, Henslee said, but Vanguard is fully committed to increasing resources in that area.

The school today has eight special education staff positions with another posted, including a student services coordinator, an interventionist, two paraprofessionals, two interventionist assistants and two special education teachers, which doubled from one such teacher last school year. Henslee did not elaborate on whether the school has further changed its approach to special education in recent years.

Teachers began taking IEPs more seriously in the classroom over the five-year course of former high school teacher Younger’s tenure, which ended in 2021. Special education teachers adopted increased autonomy, Younger said, and teachers gained a better understanding of the legal obligations attached to an IEP and how best to accommodate special education students.

The former special education teacher, who retains friendships among Vanguard faculty today, said she has heard notes of an improving culture since her departure. She said she hopes that is true.

“When I started, there was no accountability, there was no one fighting, there was no one pushing, and I started fighting and pushing,” she said. “I think we were on the precipice of change for some of the issues.”

Charter school lawyer Bethke said it’s a real concern that schools struggle to accommodate every kid with special education needs.

“It’s a universal problem that there is not enough money to really support the needs of some children with disabilities without educators and school leaders feeling like they’re taking that money from some other pressing need of the school,” Bethke said.

Even so, insufficient funding is not a recognized reason to refuse to serve students, he said.

While all schools are not equipped to handle needs in the same way, in the absence of extenuating circumstances, they are nevertheless expected to accommodate any child who enters their classrooms.

Gazette staff reporter Debbie Kelley contributed to this article.

Your Privacy Choices

Your Privacy Choices